Degeneration or denaturation of the extracellular matrix leads to loss of tissue structure or function, resulting in aging and tissue damage. The skin is no exception; age-related changes in skin structure macroscopically manifest as sagging skin, relaxed subcutaneous tissue, and wrinkles. Microscopically, these changes show loss and denaturation of extracellular matrix density.

Such skin aging is observed in the epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous fat, and mucous membranes. Weakening of structural support due to bone size reduction with aging further exacerbates the aging of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Decreased skin immunity, reduced barrier function, and impaired wound healing are also directly or indirectly affected by dermal extracellular matrix degeneration.

In the field of dermatology, active research is underway to develop procedures, medications, and cosmetics for anti-aging purposes. Various approaches are being explored — increasing collagen production and inhibiting its breakdown, increasing and supplementing hyaluronic acid production, promoting regeneration of senescent cells, and removing reactive oxygen species.

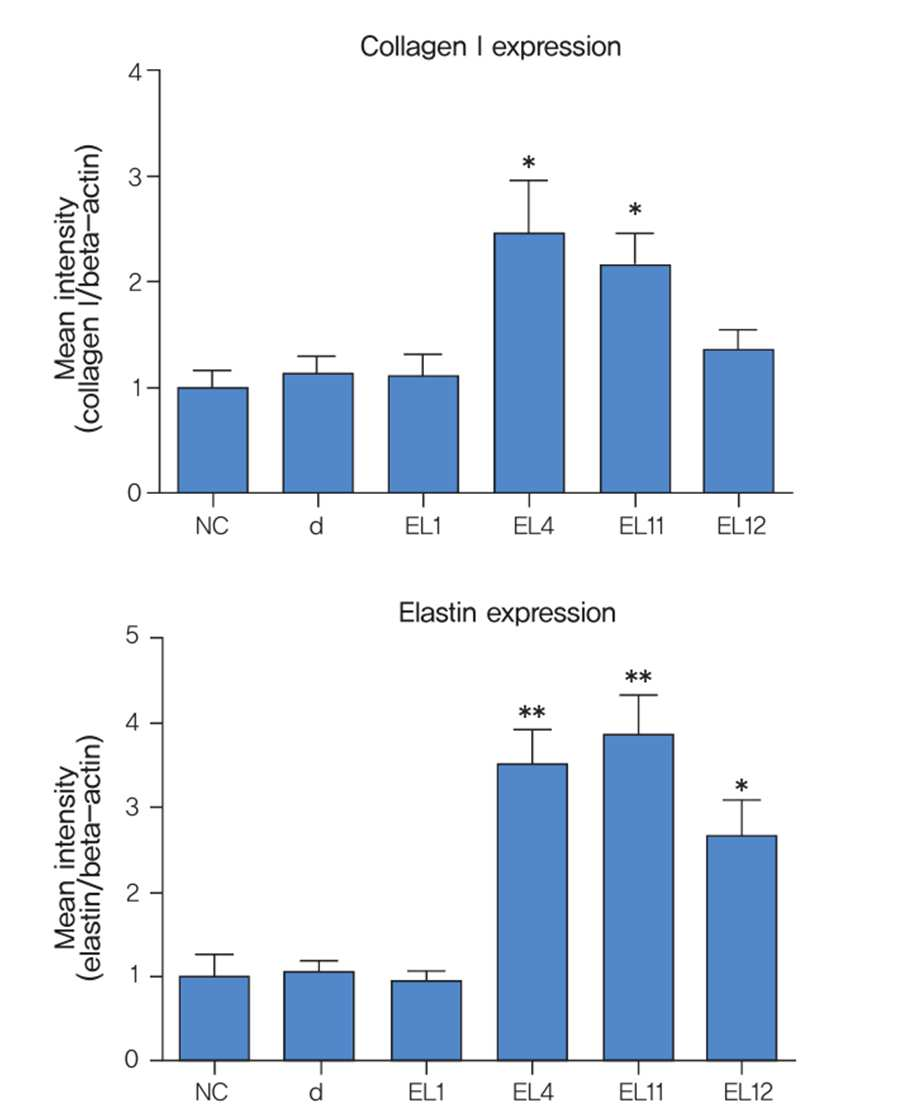

While increased collagen production is important for improving wrinkles, changes in elastic fibers and elastin also significantly contribute to skin aging. Therefore, it is unreasonable to present only increased collagen production or inhibited breakdown as the effect of cosmetic dermatological procedures or products.

Unfortunately, attempts to improve aged skin by promoting elastin production and inhibiting its breakdown have not been active until now. Recently, there has been growing interest in elastin alongside collagen, reflecting a clinical trend focused on qualitative rather than quantitative improvement of skin aging.

This article examines the histological characteristics, biosynthesis, and degradation processes of elastic fibers and elastin in the dermis and introduces a new skin booster product developed to promote neoformation of elastic fibers in the skin.

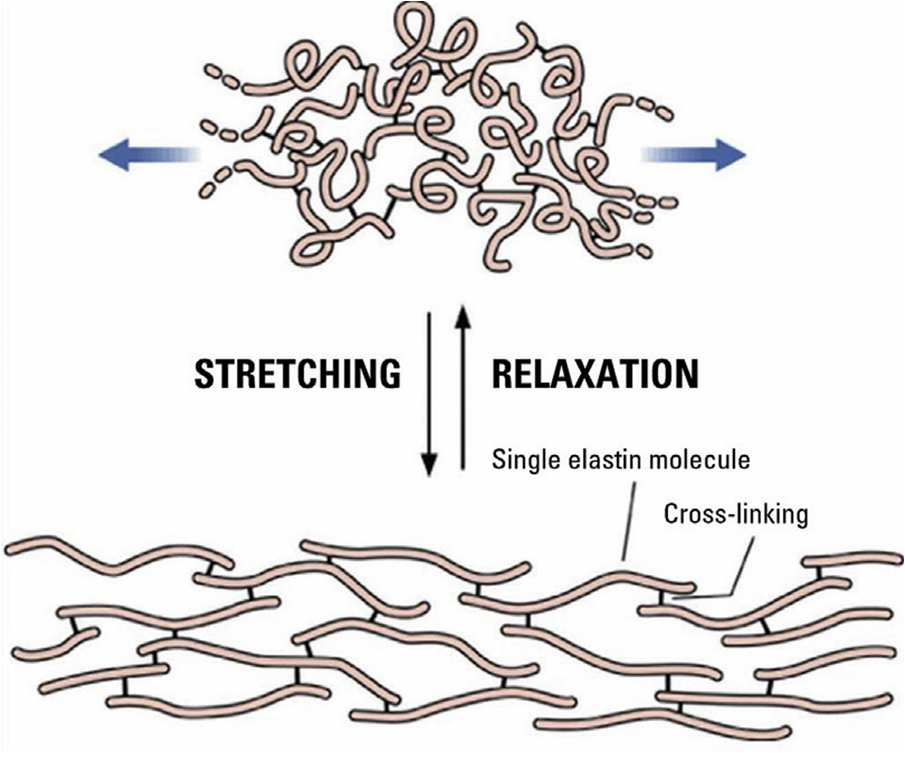

Elastic fibers are thinner and more tortuous than collagen fibers, densely arranged in the papillary dermis and sparsely in the reticular dermis. They consist of about 90% elastin surrounded by microfibrillar proteins. Elastin’s special amino acids, desmosine and isodesmosine, form cross-links that give the fibers their unique elasticity.

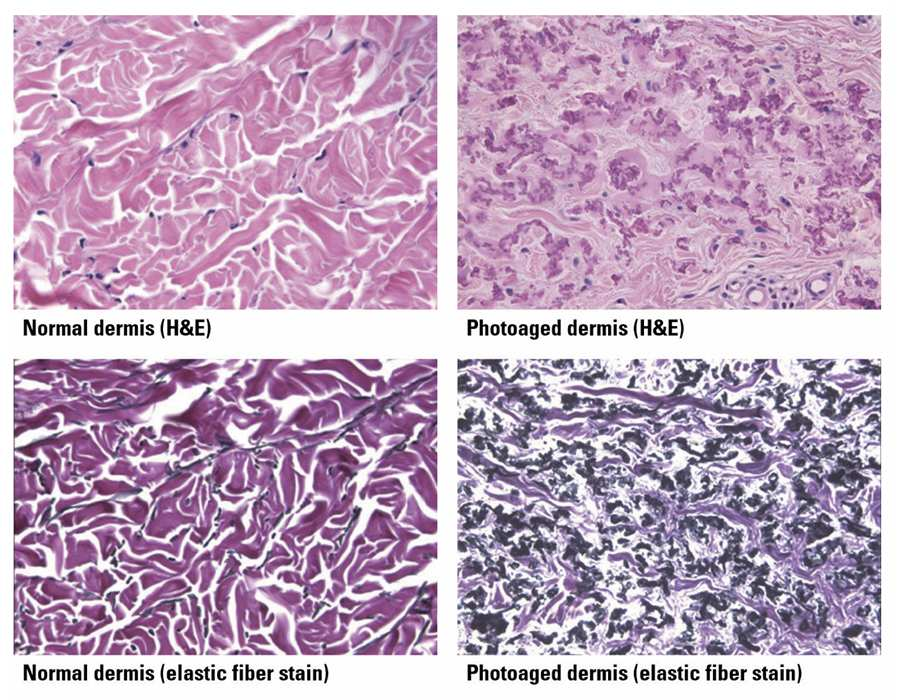

Microfibrils include proteins such as fibrillin and fibulin. Because elastic fibers are invisible under standard hematoxylin-eosin staining, special staining (like Verhoeff–van Gieson) is required for microscopic observation.

Elastic fibers in the dermis fall into three types by thickness: oxytalan fibers (upper dermis), elaunin fibers (papillary dermis), and mature elastic fibers (reticular dermis).

Changes in elastic fibers differ between intrinsic aging and photoaging. In non-exposed skin, fibers decrease in number and size; in photoaged skin, elastotic material accumulates, collagen degenerates, and the upper dermis shows matrix buildup. These changes stem from imbalanced synthesis and degradation, reducing elasticity — a hallmark of aging across tissues.

Elastic Fiber Biosynthesis and Degradation

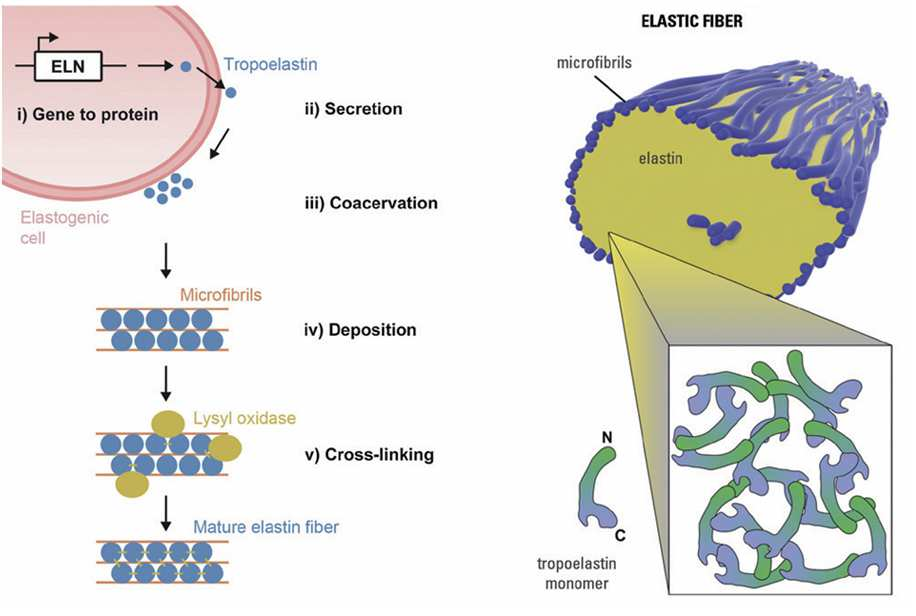

The biosynthesis of elastic fibers occurs in two stages. The first stage is the cross-linking of microfibrillar proteins produced by fibroblasts in the extracellular space to form a temporary scaffold. The next stage is the attachment of tropoelastin to this scaffold; mature elastic fibers are completed when tropoelastin is sufficiently deposited on the microfibrillar proteins.

(adapted from Yeo GC, Keeley FW, Weiss As, Adv Colloid Interf Sci 2011:167:94-103./ Schmelzer CEH, Hedtke T, Heinz A, IUBMB Lite 2020:72:842-54.)

Under an electron microscope, elastic fibers appear as electron-dense microfibrillar proteins of uniform size forming a tube, with amorphous, electron-lucent elastin filling the interior. Morphologically, elastin and fibrillin are the most important components; functionally, elastin plays a major role.

The gene responsible for producing tropoelastin, the precursor of elastin, is ELN. Human ELN gene expression begins prenatally, and by the third trimester of pregnancy, an elastic fiber network forms in the papillary dermis of the fetus. The ELN gene shows very high activity until around five years of age, then maintains a steady level for decades before rapidly declining with aging.

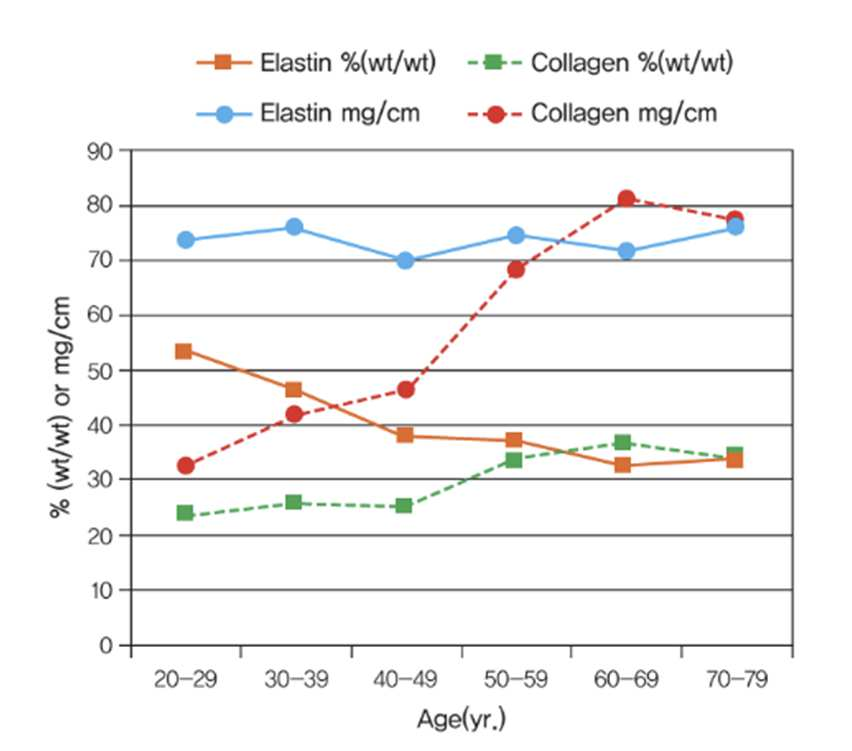

The half-life of elastin in the human body exceeds 70 years. Once formed in childhood, it is rarely replaced under normal conditions. Elastic fiber tissues in the skin, cardiovascular system, lungs, and musculoskeletal system are largely completed early in life; later, the balance between synthesis and degradation breaks down, leading to gradual degeneration and a decrease in relative concentration of existing elastic fibers.

Situations that trigger new elastic fiber synthesis in adults include damage to the skin — for example, severe photoaging. However, newly formed fibers in such cases are fragmented and entangled, forming “elastotic” material that occupies space without restoring elasticity. Therefore, the goal of promoting elastic fiber production pharmacologically or procedurally is to normalize skin elasticity, activating physiological fiber-generation pathways rather than pathological ones.

Amino Acids and Enzymes Involved in Elastin Production

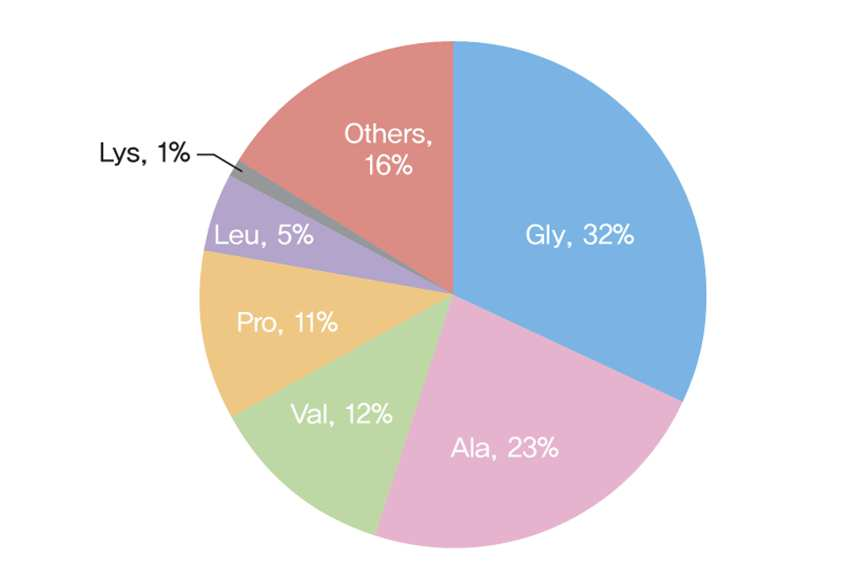

The most direct way to induce elastic fiber synthesis is to promote tropoelastin production and ensure adequate deposition onto microfibrillar proteins. The amino acids responsible for roughly 75 percent of tropoelastin residues are glycine (Gly), valine (Val), alanine (Ala), and proline (Pro). When intra- and intermolecular cross-linking occurs between these and lysine residues, a robust hydrophobic, insoluble structure forms.

Cross-linking that creates elastin is regulated by lysyl oxidase, a copper-dependent enzyme. Diseases associated with lysyl oxidase deficiency include congenital cutis laxa, whose patients exhibit lax skin, aged facial appearance, and systemic elastic-fiber abnormalities across respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, and genitourinary systems.

Although not fully understood, copper’s role as a coenzyme in lysyl oxidase activity has been demonstrated: removing copper abolishes enzyme activity, while re-adding it restores function. Menkes disease, a genetic disorder causing copper malabsorption, results in growth retardation, aneurysms, bladder diverticula, and ligament weakness—symptoms linked to impaired elastic fiber synthesis.

Mutations in the ATP7A gene inhibit intestinal copper absorption, lowering lysyl oxidase activity and thus preventing normal tropoelastin cross-linking and elastin formation.

In summary, the primary amino acids used to produce elastin are glycine, valine, alanine, and proline, with cross-linking dependent on lysyl oxidase and its coenzyme, copper.

Toward Topical and Transdermal Stimulation

Would delivering these amino acids directly to the skin increase elastic fiber production? A recent study reported improved skin elasticity after oral intake of specific amino acids found in elastin and collagen, though further verification is needed.

Topical approaches show promise: one study found that applying a peptide containing glycine, lysine, and copper (GHK-Cu) increased collagen and elastin mRNA expression. Such findings highlight a compelling avenue for dermatologic anti-aging research.

ElasticLab® Composition and Development

Would delivering these amino acids directly to the skin increase elastic fiber production? A recent study reported improved skin elasticity after oral intake of specific amino acids found in elastin and collagen, though further verification is needed.

Topical approaches show promise: one study found that applying a peptide containing glycine, lysine, and copper (GHK-Cu) increased collagen and elastin mRNA expression. Such findings highlight a compelling avenue for dermatologic anti-aging research.

ElasticLab® Composition and Development

(adapted from Smith J, Davidson E, Hill R. Nature 1963;197:1108-9.)

The amino acid composition of natural elastin found in human skin was used as a benchmark to ensure balance and efficacy.

ElasticLab® uses non–cross-linked hyaluronic acid as its carrier, providing light viscosity for dermal application. Because of its copper content (copper sulfate pentahydrate), the product has a faint blue tint.

Although approved as a cosmetic — not as a drug or medical device — ElasticLab® is used following procedures that temporarily increase skin permeability, such as microneedle rolling, fractional laser, or radiofrequency treatments, to facilitate dermal penetration.

Early Clinical Study

In the product’s early stage, a small clinical study was conducted by the author using microneedle rollers to deliver ElasticLab® to facial skin.

The study included 11 adult Korean women aged 31–72 years (average age 42.5) seeking improvement in various facial skin concerns. The main issues were decreased skin elasticity (8 subjects, 72.7%), fine wrinkles (8 subjects, 72.7%), visible pores (7 subjects, 63.6%), and uneven tone or pigmentation (6 subjects, 54.5%).

Additional conditions included melasma (2 subjects) and facial flushing (1 subject). None were pregnant or lactating.

Treatments were performed 10 times at one-week intervals. After cleansing, a topical anesthetic cream was applied for 20 minutes, followed by skin disinfection. ElasticLab® was then dropped onto the skin surface and massaged in with a 1.0 mm microneedle roller, creating micro-channels for absorption.

Half of the ampoule was applied using the roller, and the other half was delivered via sonophoresis. Standardized digital images of the face were captured using Vectra M3 (Canfield Scientific, USA) before each session, with final imaging two weeks after the last treatment.

Evaluation Methods

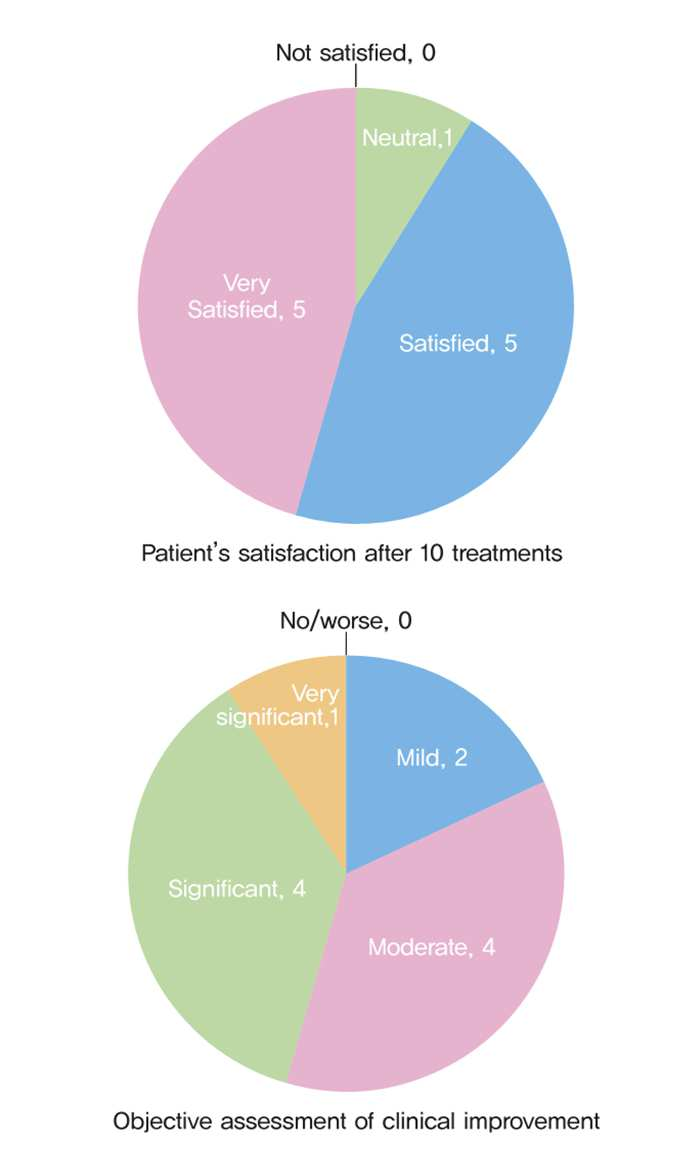

Patient satisfaction was assessed using the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) before and after the 10 treatments. Clinical improvement was evaluated through photo comparison and quantitative analysis via Vectra Analysis Module and Image software.

During and after the procedure, participants reported minimal discomfort.

Clinical Results and Observations

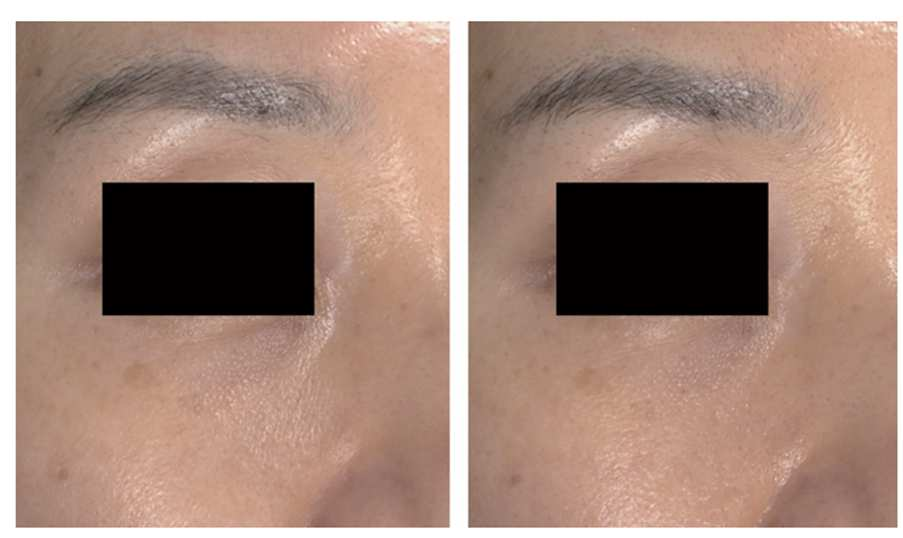

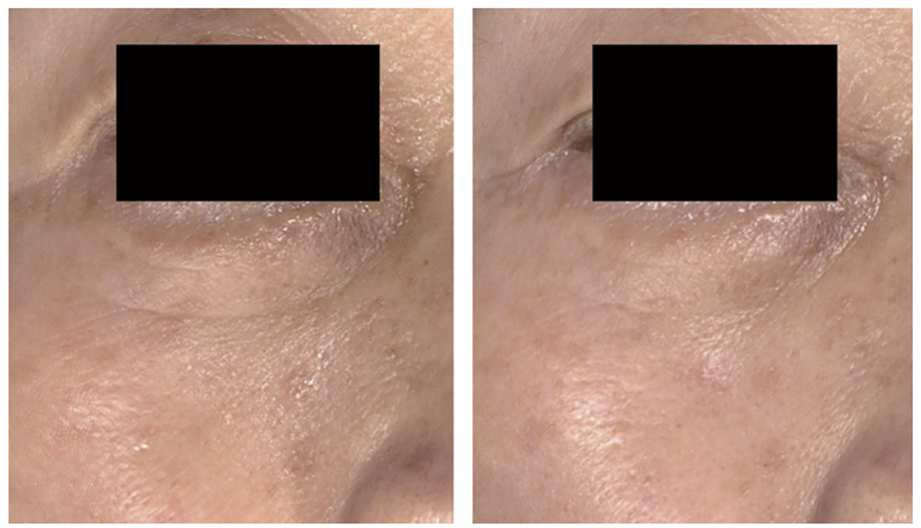

The study results showed that 10 out of 11 subjects were satisfied with the treatment effects. Objective evaluation through clinical photographs indicated moderate or greater improvement in 9 subjects.

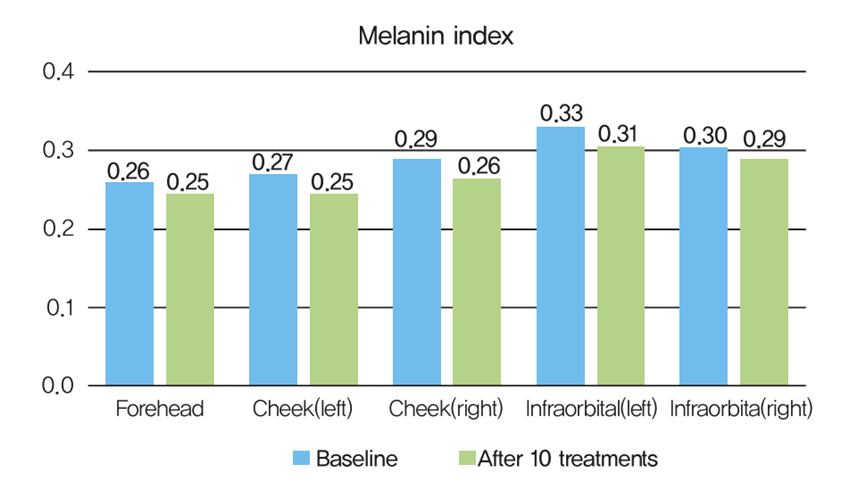

The melanin index decreased after 10 treatments, with the largest change observed in the cheeks (−8.9%), followed by the undereyes (−6.3%) and forehead (−5.8%).

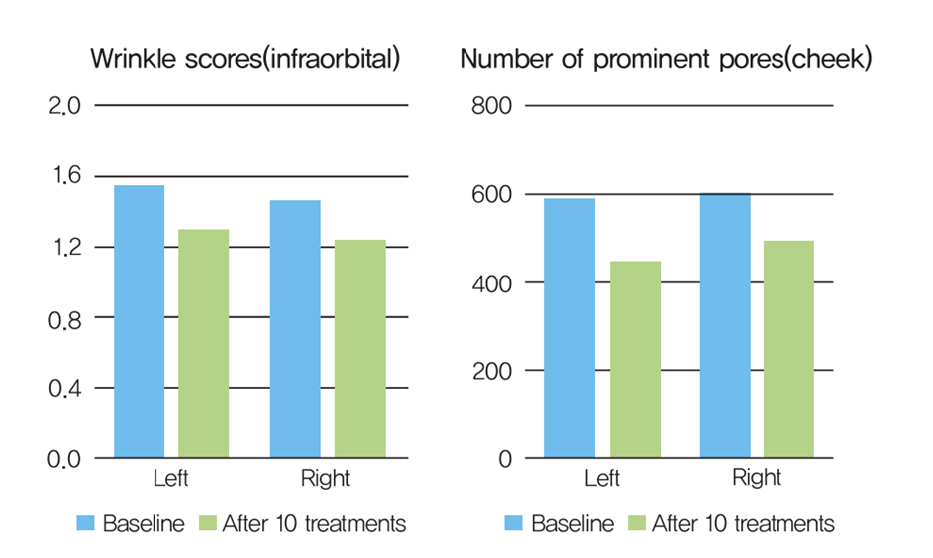

The wrinkle index of the infraorbital skin decreased by 15.5%, and the number of prominent pores on the cheeks decreased by 21.3% on average.

Women in their 40s tended to show higher subjective satisfaction with overall improvements in skin tone and texture.

In older age groups, infraorbital fine wrinkle reduction was particularly notable.

Post-treatment discomfort was minimal. All participants experienced mild erythema after treatment, which lasted an average of 1.4 days. Temporary skin dryness occurred in some cases, lasting about 2.5 days on average. No participants reported adverse side effects.

Clinical Results and Observations

Clinical results demonstrated that transdermal delivery of ElasticLab® using microneedle rolling and sonophoresis effectively improved skin tone, texture, infraorbital fine wrinkles, and cheek pores in adult Korean women.

Given the minimal pain or discomfort during treatment and the absence of post-procedure complications, this approach is recommended as a repetitive, steady anti-aging procedure suitable for dermatology clinics.

Because skin permeability temporarily increases for about 4–6 hours after treatment, the choice of home-care products applied post-procedure can further enhance outcomes.

It is also believed that using more advanced transepidermal drug delivery systems — such as fractional lasers or radiofrequency devices — to introduce ElasticLab® into the dermis may yield even stronger anti-aging effects. Further research is encouraged in this direction.

Korean Dermatological Association Textbook Compilation Committee. Dermatology, 7th Edition. Jungwoo Medical, 2020.

Korean Dermatological Association Textbook Compilation Committee. Dermatology, 7th Edition. Jungwoo Medical, 2020.

-

Heinz A. Elastic fibers during aging and disease. Ageing Res Rev 2021;66:101255.

-

Schmelzer CEH, Hedtke T, Heinz A. Unique molecular networks: Formation and role of elastin cross-links. IUBMB Life 2020;72:842–54.

-

Reddy B, Jow T, Hantash BM. Bioactive oligopeptides in dermatology: Part I. Exp Dermatol 2012;21:563–8.

-

Smith J, Davidson E, Hill R. Composition of normal and pathological cutaneous elastin. Nature 1963;197:1108–9.